Un engagement à 100%

Promotion de la sécurité En Australie, la grande majorité des sites miniers extraient les ressources à l’aide de machines et d’équipements modernes. Or, une mine de l’État de Victoria fait encore appel aux procédés manuels tout en affichant un très haut niveau de sécurité.

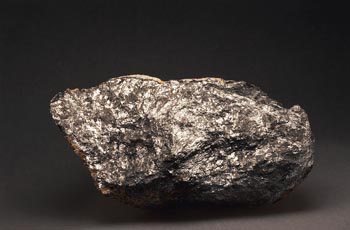

Mandalay Resources Corporation’s Costerfield underground mine, located in central Victoria just 100 kilometres north of Melbourne, produces gold and antimony from an ore body that is on average only 300 millimetres wide – necessitating the use of narrow-vein hand-held development and stoping.

About the Costerfield gold-antimony mine

Costerfield mines gold and antimony. In 2011 it mined more than 66,000 tonnes of ore, producing 12,914 ounces of gold and 1,539 tonnes of antimony. The mine is centred on the small settlement of Costerfield in central Victoria, Australia, about 10 kilometres northeast of Heathcote, 50 kilometres east of Bendigo and 100 kilometres north of Melbourne.

It produces ore from a single underground mine exploiting the steeply dipping Augusta East, West and North lodes at the south end of the main Costerfield zone. Ore is accessed by a spiral 4 by 4 metres decline grading 1 in 8 from the surface.

Mining in the upper levels consists of extraction of remnant ore and pillars left by underground mining prior to 2009. Mining on the new levels is accomplished by cut and fill and cemented rock fill blast-hole stope methods at a 1.8-metre minimum width.

Ore is trucked on the surface, where it is stockpiled and blended into the crusher. Concentrate is shipped to the port of Melbourne, and from there to smelters in China.

That requires the mining at the face to be carried out manually by crews of miners using air-operated drilling equipment, working 12-hour, seven-day shifts, according to Mel McCarthy, mine manager at Costerfield.

For McCarthy and her entire team at Costerfield, the challenge is to ensure that everyone at the mine – not only those working manually at the face, but also the crews working the loaders and trucks, along with those providing the support services – all work to the highest safety standards.

“We are 100 percent committed that people don’t get hurt and that we do things safely – and we will stop any job if people are concerned about safety,” McCarthy says. “Safety must come before production. The community expects it, so in Australia – and in Victoria in particular – the mining industry has come a considerable way in the past decades to make sure that this happens.

“That means anyone can walk in my door and tell me anything, and that’s fine,” she says. “If it’s to do with safety, they don’t have to go through the hierarchy of the organization. So if they think they are not being heard by their supervisor or if they are not being heard by the next level up, my door is always open. All of our leadership team have the same approach, whether it’s in terms of being open to people’s ideas about different ways of doing things, or if they are concerned about an unsafe condition.”

McCarthy says this also applies to those working in the mine.

“We have a very strong safety culture and safety awareness inside the mine,” she says. “An important part of their work is looking after each other – something which applies throughout the world, in that miners are always looking after each other and their safety, to make sure that their mate is okay. The guys at the face are acutely aware of conditions – what they see, feel, smell – so as mine managers we have to be open to listening to what they are saying.”

But Costerfield’s commitment to the safety and well-being of its miners doesn’t end at the mine gates.

“We pay for our miners to go and see muscular-skeletal specialists on their days off,” McCarthy says. “They work seven days straight and then they have seven days off to recover, and during that time they see specialists for massages, acupuncture and other treatments to help them to maintain their bodies. We are finding that’s working really well in terms of supporting them.”

The mine also has an intensive training programme teaching the drill operators how to use their drills without injuring themselves or causing longer-term damage to their bodies.

“The drills weigh about 60 kilograms or more, and it takes about two years to get really skilled at using them,” McCarthy says. “While all our face operators are men, they don’t necessarily have to be big and strong to operate the equipment. We’ve got a combination of some really muscular guys and we have some really good guys that are slightly framed and they can do it just as well. The secret is in the balance and the technique.”

In the longer term, however, Costerfield is aiming to move away from manual mining.

“There are still probably a few mines in Australia that do this sort of manual mining, and we all have to rely on the historical way of doing it, because there are no machines on the market that can do it as efficiently as a person can in such narrow veins,” McCarthy says.

“Currently we have an R&D project – and Sandvik is starting the ball rolling on what is available to mine in these conditions – so we can mechanize the means to drill and bolt these narrow drives.”

In the end, every aspect of Costerfield’s operations comes back to safety.

“Safety counts above all else, because if you don’t have a safe mine, you can’t operate,” McCarthy says. “That is what the staff expects and the regulators expect and the government expects.

“My experience in mining around Australia is that safety really depends on the management shown at a site. Management is the key driver for the culture, so if you haven’t got good leadership on a mine site, that’s when risks get taken.”

At the same time, McCarthy is a firm believer in the principle that having a good attitude to safety enhances productivity.

“I would say that a safe mine is a productive mine,” she says. “A lot of mine injuries are caused by things that can be put down to poor housekeeping standards. If the culture can be managed such that everybody cleans up after themselves, everybody does the job properly and nobody takes shortcuts, ultimately that is going to increase productivity. But it also improves your safety performance, because people don’t trip over things that they haven’t cleaned up – and that is one of the biggest issues in underground mining because of the confined space.”

One of the biggest changes in safety that McCarthy has seen over her 15 years in the industry is the move away from highly prescriptive safety requirements – where everything is laid out in black and white through government laws and regulations – to a risk-assessment process.

“The risk assessment–based system puts the onus back onto the operator of the mine to risk-assess everything, rather than to take the approach of doing things by the book and making sure that they are following the rules,” she says. “I think it forces far more proactive thinking about what you are doing.

“But with this risk-assessment approach, I think there is also an argument that the way the industry is at the moment, due to the mining boom and resulting skill shortages, there is a chance you may have a lot of inexperienced people running mines who may not know what all the risks are,” McCarthy continues. “I also think that the increased litigation that is happening everywhere is discouraging mines from sharing learnings, and that has been more of a negative thing over time. If people don’t share what has happened at their mine, then we don’t learn from each other. Unfortunately, I think we are really poor at that.

“But comparing industries, for example, in Victoria last year, 17 farmers died on their farms – and nobody died in mining. However, if just one person had died in a mining accident, there is a very good chance that mine would be shut down. So having an unsafe mine is unsustainable – and you can’t operate unless you are safe.”

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F01%2F100percent-slide3.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F01%2F100percent-slide2.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F01%2F100percent-slide1.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F08%2FADSC_6407_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F08%2FADSC_6401_B_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F08%2FLH514BE_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F07%2FSandvik-DS412iE-04-01_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F06%2FArlene-illustration_high_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F06%2FMining-Machine-Exploded_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F06%2F91320802_xl-fix_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F05%2FDD2711-2-justerad_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F05%2FA10-underground_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F05%2FNAPO191113AL_031_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F04%2FSolid_Ground_Riccardo_Losa-1050482_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F04%2FLeopard-DI650i_49625_1600x570.jpg)