Back from the break

Österbybruk, Sweden. Almost 20 years after it was closed in 1992, the reopened Dannemora mine in Sweden has just secured its first long-term contract for iron ore. But getting an old mine back in business again has its challenges.

AT 460 METRES below ground, time has frozen. In the underground service workshops, loaders and drills stand covered with a patina from years under water. An old football pools coupon with matches played years ago litters one of the drifts. In a collapsed changing room, somebody’s coffee mug lies on the floor. Everything has been left where it was in 1992 when low market prices for iron ore forced the mine to shut down, switch off its drainage pumps and let the water rise.

“We need to scale away everything in this area,” says development manager Michael Meyer, who heads the work with access drifts in the mine. He must make sure there is enough space for the new mining machines that will be serviced here. “The old workshops are conveniently located, but the entrances are too narrow for today’s requirements,” he says.

Dannemora mine

Location: 100 kilometres north of Stockholm and 38 kilometres from the Baltic Sea coast.

Type: Underground iron mine.

Product: Magnetite ore delivered as fines and lump ore.

Planned Capacity: 1.5 million tonnes per year by the end of 2013.

Employees: Around 130 when the mine reaches capacity.

Known reserves: 28 million tonnes in about 25 ore bodies.

Owner: Dannemora Mineral, founded in 2005 to reopen the Dannemora mine, which was closed down in 1992.

It has been more than a year now since the water was pumped out of level 460, and to the untrained eye it is difficult to visualize these damp and slippery drifts, crammed with old equipment, as an operating workshop. But in 2005, when Nils Bernhard and Lennart Falk founded Dannemora Mineral, the same thing could perhaps be said about the whole mine. Both are entrepreneurs and private investors, Bernhard with degrees in engineering and economics and Falk with a Ph.D. in geology. At the time, market prices for iron ore had doubled since the end of the 1980s, not least due to demand from China. Prices were still rising, and the two saw an opportunity to get the abandoned mine back in business.

Bernhard and Falk knew the ore was there, but before they could bring it up for sale they needed to secure a few things: a concession, a number of permits and a completely new mining infrastructure, for example. Still, only six years later Dannemora has just secured a five-year contract from 2012 for up to 300,000 tonnes of iron ore to German steel manufacturer Salzgitter Flachsta.

“We will sign more contracts in the near future and expect them to cover our production,” says Kjell Klippmark, managing director at Dannemora Magnetit, a daughter company doing the actual mining. “When the crushing plant and skip hoist are ready by the last quarter of 2013, we will have a maximum hoisting capacity of 2 million tonnes per year.”Until then, the ore will be hauled to the surface by trucks and crushed there, a temporary solution that would be too costly during regular production.

When the operation closed in 1992, ore had been mined there since the 15th century. Over the years about 25 ore bodies were mined in an area of three kilometres square. Today, the remaining ore potential in and around Dannemora is estimated at more than 28 million tonnes.

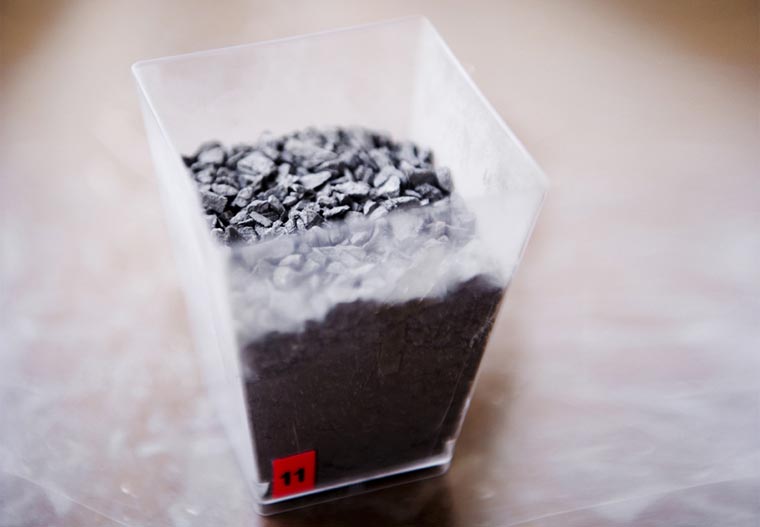

Dannemora delivers magnetite as lump ore from 5-16 millimetres and fines in sizes of 5 millimetres and below. Since the ore contains manganese, the prospective buyers are steel mills that need this as an alloy material. “We want to be a niche supplier providing perhaps 5 to 10 percent of what goes into their furnaces,” says Klippmark.

As head of Dannemora Magnetit, he is responsible for raising the mine from the ashes. The initial work has been divided into five large projects: new surface and underground infrastructure, a new sorting plant, developed mine ramps, adequate mine ventilation and a new skip hoist.

Dannemora’s equipment list:

- 2 DD421-S60C twin-boom mining jumbos

- 2 DL421-7C production drill rigs

- 1 DL421-15C production drill rig

- 1 DS410-C mechanized rock bolter

- 1 DB120 boulder splitter

- 6 LH517 loaders

- 2 CH440 cone crushers

- 1 CS430 cone crusher

Dannemora has the advantage of a railway line to Hargshamn, a port on the Baltic Sea just 38 kilometres away. The infrastructure project includes the renovation of the railway and construction of new terminals at both ends. When Solid Ground visited the mine, a brand new railway track encompassed the ore yard. It runs through a recently built concrete structure that will house silos, from which the railway cars will receive their loads. Access roads for heavy traffic and an upgraded high-voltage power supply are also part of the infrastructure package.

By March 2011 the founders and other investors had put SEK 935 million (103 million euros) into the Dannemora venture. But human capital is also necessary to get the mine going. Dannemora Magnetit AB currently employs around 30 people, mainly in management and expert positions. An additional 100 to 150 are employed by contractors doing most of the work during the initial investment phase. That number will gradually drop as the projects are finished.

When regular production starts by the second quarter of next year, 30 more people will be employed directly by the mine, and as full production starts towards the end of 2013, another 60 should have joined their ranks.

Dannemora is now trying to find the right people for the jobs and has so far arranged two recruitment days. To get a more even gender distribution in the mine, the first recruitment day was reserved for female applicants.

“Our goal is that at least one-third of our employees should be women, and this is what we are aiming for,” says Klippmark, who plans to provide separate changing rooms and toilets.

This brings us back to level 460, where development manager Michael Meyer has this and other things to think about when planning the underground facilities. After a 30-minute ride in a provisional lift up the 620-metre main shaft, we reach the surface and get into a car to check on the progress of the main ramps.

There are two of them, one from the surface to level 350 and one from there to level 460. Winding down through the ground, they total around 4.2 kilometres in length. This is where both miners and machines will enter. We pass the entrance as we drive down an old ramp, too narrow for modern equipment, to a drift that has just entered the Botenhäll ore body at level 143. A scent of ammonia hovers in the air after the latest blast, but at the end of the drift we see what has drawn people here for centuries – black, shimmering iron ore.

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F01%2Fbackfromthebreak-slide3.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F01%2Fbackfromthebreak-slide2.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F01%2Fbackfromthebreak-slide1.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F02%2FNAPO191125AL_068_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F02%2FRegis_mill_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F02%2FNAPO191121AL_005_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F02%2FSandvik-ACS-Automation-Connectivity-System_53036_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F08%2FNAPO181010AL_014_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F06%2FNAPO180903AL_066_1600x570.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F04%2FEl-Teniente_c1.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F01%2FGGAO3832_hires.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F08%2F1_NAPO140403AL_075_b1.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F08%2Fnapo130625al_double.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fsolidground.sandvik%2Fwp-content%2Fthemes%2Fminestories%2Fimg%2F%2Fplaceholder.jpg)